Trigger warning: pregnancy loss

Thirty-seven weeks and two days.

That’s how far along educator Takiema Bunche-Smith was in her pregnancy when her midwife told her she couldn’t find her son’s heartbeat.

Bunche-Smith, 39, shares how she rallied from the devastating loss of her firstborn Nazir, and how she’s using her experiences to raise her 7-year-old son Na’im and teach the next generation of learners.

The familiar strains of Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal” start up from Na’im Smith’s iPod. Not one to miss his cue, Na’im rushes to the center of his living room, ready to give his audience the show of a lifetime.

Fedora cocked and dress pants hitched up high, he moves across the floor, humming along as he pops and spins just like his idol.

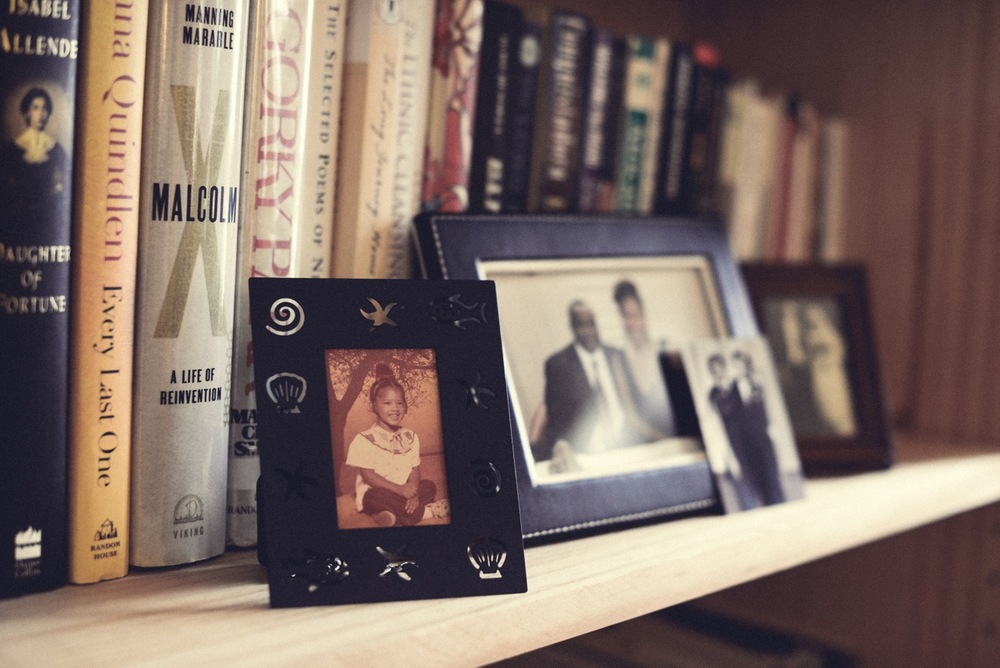

Takiema Bunche-Smith laughs as she watches her little ham dance. Though he most resembles his father David, Na’im is his mother’s son. The two are constantly moving (combined they probably have enough energy to power two New York City blocks); both are incredibly inquisitive and prone to spouting off random facts.

“He was a firefighter on Halloween for two years,” Bunche-Smith says. “The second year we gave out firefighter fact cards instead of candy. Did you know that there’s 500 gallons of water in a fire truck?”

Every moment is a teachable moment in their home: When Na’im noticed a new bird call outside their apartment window, the family planned a field trip to the Audubon Center in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park to determine what type of bird it was.

It makes sense given Bunche-Smith’s decades-long career as an educator—she’s currently the director of curriculum and instruction at the Brooklyn Kindergarten Society, a nonprofit organization that brings private-school quality preschool education to children living in some of New York’s most deprived communities.

“Education chose me,” Bunche-Smith says now. “There’s no other way to describe it. I’ve always loved children. I knew that I wanted to work with children in some way, shape, or form.”

Bunche-Smith received her bachelor’s in psychology from Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, and then got her master’s in early childhood education at the Bank Street College in New York City. She worked as an assistant teacher for 3 and 4 year olds at a progressive, child-centered school affiliated with the college.

Teaching at the Upper West Side school definitely gave Takiema Bunche-Smith some culture shock—children were treated as equals in ways that sometimes went a bit too far in her opinion. But, she credits her time as invaluable to her career.

“That was when I started to understand different ways of teaching and learning,” she says now. “I was there for two years, and I [thought], Okay, I’m ready to go to the hood and take some of this stuff to Black and brown kids.”

Given Bunche-Smith’s love of children, there was never a doubt that she and David were going to have a family of their own. In 2003, the pair were thrilled to find out that Bunche-Smith was pregnant with a baby boy. Each passing week brought more and more excitement for Nazir’s arrival.

Bunche-Smith flips through the pages of a nearby photo album before stopping on pictures from her baby shower. She’s 34 weeks pregnant then, her smile huge and her stomach round underneath a white long-sleeved shirt. But as she flips the page, a shadow passes over her.

“[At] 37 weeks I started feeling strange for a few days,” she recalls. “I had a midwife appointment and I called and said, ‘I don’t feel right. Something feels weird.’

“I asked to come in earlier,” Bunche-Smith continues, “and when I went in she couldn’t find the heartbeat. So she said, ‘I’m going to send you over to the hospital for a sonogram. Maybe the baby just moved in a weird position.’ I went there and they couldn’t find the heartbeat. I was 37 weeks, 2 days pregnant… They knew that he had died, so I had to give birth to him [on that day, December 2, 2003].”

She stops for a moment, blinking back tears.

“My path to motherhood was a much-wanted pregnancy, a much-prepared-for child, and [then] three weeks before he was due, he died.

“I definitely cry because it’s a very difficult thing that lives with you for the rest of your life,” she continues. “It’s the only kind of death [where you] experience life and then death inside of you. What you have is your hopes and your dreams and your sense of your child’s spirit. And so to have that go, and not have a chance to explore it… To have to give birth and have no baby, and to [be] postpartum… There are not any words for that.”

After Nazir’s death and stillbirth, she was “very fragile.” Bunche-Smith found support in her family and from a number of support groups for women who also experienced late-term losses. While many mothers she spoke to were ready to have another baby “immediately,” it took Bunche-Smith 13 months of “very deep grief work” before she would consider it.

“Over time I just realized that I wanted to be a mother to a living child so badly that I was willing to take the risk of this happening again,” she says. “When the thought of not having another child was more terrifying to me than trying to get pregnant and potentially losing another pregnancy, I knew I was ready to try again.”

In January 2005, Takiema Bunche-Smith learned she was pregnant with Na’im. Seven years later, her love for both of her sons has only deepened.

“Nazir…was a part of our family. More than anything, I think [he] shaped the kind of mother that I am,” Takiema Bunche-Smith says.

“People always tell moms ‘Cherish every moment, and pay attention to the small things, because the moment you look up, they’re going to be taller than you…’ Nobody ever has to tell me that. Even when I’m upset and we’re fussing and things aren’t going the way I want, there’s a part of me that’s like, This is such a gift to me, to mother you and to have this experience and to have my house be a wreck right now. There’s always a small piece of me that says, Thank God. Thank you for being here, thank you for giving me this experience.”

Q&A

THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR SHARING YOUR STORY WITH US. DO YOU MIND SHARING HOW YOU FELT WHEN YOU FIRST SAW NAZIR?

He was beautiful and he looked like a sleeping angel. He looked like a combination of me and my husband.

I remember his feet. I told my husband, “Thank God he got my feet.” We laugh-cried. Like, we’re so happy to see our baby. We love you, we’ve been waiting for you, and, Oh my God, open your eyes. How can this be reality?

It was literally alternating between smiles and sobs. Bittersweet doesn’t even begin to cover it.

DID YOU EVER FIND OUT WHAT CAUSED THE COMPLICATIONS IN YOUR FIRST PREGNANCY?

About 70 percent of stillbirths are unexplained, so I think we just put it into that category. I did have some health problems when I went in for the induction. My blood pressure was dangerously high so I had preeclampsia, which can be fatal to both mom and baby. So they thought it may have been the preeclampsia.

When I got pregnant the second time in 2005, I became obsessed with reading medical literature on stillbirth and pregnancy. Sometimes I would get strong intuitive feelings about whether or not some of the things I was reading related to me. I came across something about blood clotting disorder, so I went to my midwife and I said, “I need you to test me.”

In all the testing that I had after the stillbirth, that was the one thing that I hadn’t been tested for. And ding ding ding, it came up. I have a genetic mutation. One of my genes causes my blood to over clot. When you’re in pregnancy, your blood tends to clot more, but I have a gene that makes my blood clot even more, which prevents nutrients from getting to the baby. It’s also what predisposed me to not having proper blood flow, which led to the preeclampsia.

After that discovery I was co-managed between the midwife and a perinatologist. I was able to deliver Na’im safely—also with an induction, because with the monitoring it came up that at 37 weeks, my blood started looking pretty wonky again.

HOW DID YOU FEEL WHEN NA’IM WAS BORN?

The depths of my sorrow for losing Nazir were completely paralleled by the heights of my joy for having Na’im. It was the exact opposite, but it was also coupled with grief again. I thought, Remember what happened last time and what you lost? Look how amazing this is. You could have had it twice.

But the joy when I was able to just focus on him being here was incredible. I still remember that feeling of trying to nurse. It was so hard, but I was like, “I don’t even care. We’re going to work it out. You’re here. Oh my God: You pooped! Yay! You’re alive!”

You don’t get to parent a child that’s died in the same way, but I was more confident in knowing that I parent Nazir through telling his story, and just being who I am as a mom and supporting other moms.

WHAT DO YOU LOVE MOST ABOUT BEING A MOM?

Oh God, I can’t pick one thing! I will say that as an educator, I’ve really enjoyed having this child in my own home. To see the information that I’ve had in my head for a long time and implemented with other people’s children come to life in my own child has been really rewarding and really humbling. (Laughs)

The rewards have been amazing, but then on the other hand, he does shit that I’m like, “I’ve never seen this before, this doesn’t match with anything that I’ve seen or any book that I’ve read.”

WHAT’S THE MOST GRATIFYING PART OF YOUR JOB?

I’m trying very hard to implement a private, high-quality preschool experience for children in the projects. We have really high standards—academic and otherwise—and we have a very rich program for children that is based in social studies, science, the arts, and hands-on learning.

In one of our centers, they’ve started composting with worms indoors; we have garden boxes and so many rich experiences for children. The centers are housed in the projects, and many of the children live in the projects, or within the surrounding neighborhoods, and don’t have access to so much. I’m so excited that they get to have these experiences with us—and to grow as much as they do when they’re with us—because I know a lot of children don’t get that. Some daycares sort of ignore the kids; our kids are getting academics, but they’re doing it through play.

IT’S SO GREAT THAT YOU’RE CREATING THESE KINDS OF EXPERIENCES FOR YOUR STUDENTS!

I am so interested in what we are doing with children during the day. How are we helping them to understand and be critical of their communities and our world? Some schools think we need to get them to memorize things, but do you want them to just press the buttons on a cash register when they grow up?

Let’s think about that.

When you’re 17 and you’ve been listening to people tell you what to do and how to do it your whole life, and you don’t know how to make decisions, you’re limited in so many ways. I want our children to be able to say something beyond “I want to be a rapper or basketball player.” What about an artist, an engineer, a pilot, a teacher? I really think that education is a political act.

“EDUCATION AS A POLITICAL ACT.” CAN YOU EXPLAIN WHAT YOU MEAN BY THAT?

If you help a child to look at the world critically, you have lit a fire and given them an approach and a disposition towards learning—the possibilities are endless.

When I was teaching first grade at this public school in Williamsburg, there were lots of Puerto Rican and Hasidic children living side by side, but they never interacted together more than just superficially.

There was a boys’ Yeshiva [Editor’s Note: a Jewish school] attached to our playground. Some of the Hasidic children started coming up to the fence and yelling out curses at our children, spitting, finding pieces of paper to throw…

One by one, the kids would say, “Ms. Bunche, the Jewish kids are yelling curses!” They were getting really upset about it. I remember the second or third day it happened, we went back to class, we sat down, and we had a meeting.

I said, “Kids, we have a problem going on. Who wants to share?”

Everybody said, “He said this to me, and he stuck out his tongue, and he said an S-word!”

And I said, “Well, what should we do?”

I encouraged them to write and draw their feelings about what happened, and went over to the Yeshiva with their letters.

Do you know the next day that principal ran over to the classroom? He said, “I’m so sorry! I can’t believe this. They will never do that again.”

He left and the kids started cheering! They were saying, “We did it! They’re not going to bother us anymore!”

I said, “Well, it sounds like we need to tell our friends what just happened, and what they can do if they have a problem, because your words are really powerful.”

They went around to all the classes, even the fifth grade, and said, “If you have a problem, you can write a letter and then somebody can help you!”

For me, that kind of illustrates this idea. I could have just yelled at the boys who were taunting my students, but that wouldn’t have taught them or my students anything at all. I got my students to express their feelings and have them validated by adults around them. I told them, “You’re 6 and 7, but look how powerful you can be. Your pictures and words had this principal come running over. He really wanted to respond!” That’s powerful and empowering.

HOW DOES YOUR CAREER AS AN EDUCATOR INFORM THE WAY YOU PARENT NA’IM?

My parenting philosophy is completely in line with my education philosophy. I believe that all children are incredible people with a wide range of emotions and interests. They deserve the respect of adults and other children around them and to be supported as they explore and as they create.

So that’s my parenting philosophy for Na’im: that he’s a worthy human being. He’s going to be angry, he’s going to be sad, he’s going to be jealous. My job is to give voice to that for him, to name it for him, and to help him think about what that means.

Our interview with Takiema Bunche-Smith has been edited and condensed for clarity.