Like many of us, I saw the Mario Testino-shot photos of Serena Williams and her daughter Alexis Olympia Ohanian, Jr. before I read the feature. And I had the reaction I’m sure Anna Wintour and the rest of the Vogue team expected:

Yaaas to that snatched waist and Coca-Cola bottle frame sheathed in a fire-engine red Versace dress.

Squeal over little Olympia’s big brown eyes looking directly at the camera with her mother reclined next to her in a lilac and pink Valentino number, looking regal AF. Looking like Easter morning.

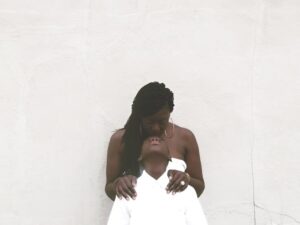

Here was a powerful woman enveloped in maternal and newlywed bliss, the very picture of love.

The feature focused on Williams navigating what this new-found joy could mean for her hard-fought-for career. It’s a story of work-life balance and new mom transitions familiar to many working and aspiring mothers.

But along with the quotes of her love for her daughter and the temptation to focus on motherhood over tennis, another common tale appeared.

One of a Black woman having a traumatic birth experience.

One of a Black woman being ignored when advocating for her health and showing bodily agency.

One of a Black woman avoiding a fate that has befallen so many of her sisters: dying after childbirth.

As a superstar athlete and as someone with a history of pulmonary embolisms, Williams knows when something is wrong with her body. The day after an emergency C-section, she experienced a shortness of breath that she knew signaled a possible blood clot. The following text from the Vogue feature describes what happened next:

She walked out of the hospital room so her mother wouldn’t worry and told the nearest nurse, between gasps, that she needed a CT scan with contrast and IV heparin (a blood thinner) right away. The nurse thought her pain medicine might be making her confused. But Serena insisted, and soon enough a doctor was performing an ultrasound of her legs. “I was like, a Doppler? I told you, I need a CT scan and a heparin drip,” she remembers telling the team. The ultrasound revealed nothing, so they sent her for the CT, and sure enough, several small blood clots had settled in her lungs. Minutes later she was on the drip. “I was like, listen to Dr. Williams!”

In that paragraph, those of us who know saw a Black woman who had narrowly escaped what the medical community calls a “near miss”—that is, when a woman suffers complications so great that she almost dies during pregnancy, childbirth, and/or postpartum, which happens to around 65,000 women in America.

A Perfect Storm of Bias

Black women around the world read those sentences and remembered their own traumatic birthing experiences or gave thanks that Serena Williams didn’t suffer the same fate as loved ones who didn’t survive childbirth. (About 700-900 women a year die from “causes related to childbirth,” according to ProPublica, making the United States’ maternal mortality rate [MMR] extraordinarily high compared to other countries. America also has the distinction of being the only industrialized country with a worsening MMR.)

Death is the great equalizer of us all, but not when it comes to maternal mortality. That’s something that Black women experience at ridiculously higher rates than women of other races. Black women are two times more likely to experience near misses than white women, according to a report in Essence, and the CDC stat of our being three to four times more likely to die than our white counterparts has become a worn and sad battle cry. To make that chasm even clearer, that means that we are “243% more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes,” NPR and ProPublica reports. Black women’s criminally high maternal mortality rate is the reason why America’s MMR is so high.

There are so many risk factors that disproportionately affect Black women of all walks of life and highlight the systemic racism that informs policies and health outcomes. (ProPublica’s investigation had the title and subhead “Nothing Protects Black Women From Dying in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Not education. Not income. Not even being an expert on racial disparities in health care.”)

We experience higher instances of living in poverty or with obesity, diabetes, fibroids, and hypertension. We have less access to quality health care and insurance and food, and more exposure to chronic stress. (While black don’t crack, our genes tell a different story—”black women in their 40s and 50s appeared 7.5 years older on average than those of whites” in our telomeres, the part of our chromosomes associated with cellular aging. Shorter telomeres are connected to poorer health.)

We can’t afford to wait for policy to catch up with human decency. Lives are literally at stake.

It seems like pregnancy becomes a perfect storm when these health factors meet the healthcare systems’ bias and racism, leaving traumatized Black women and their families in its wake. Doctors and nurses’ biases against pregnant women of color are well-documented—in a 2013 survey conducted by Listening to Mothers, 1 in 5 Black and Latinxs reported poor treatment from hospital staff, compared to 8% of white women. This bias seems to be the first tipped domino that leads to and postpartum deaths. Especially considering that 60% of maternal complications are preventable, according to the CDC Foundation.

Black Mamas “Battling Over Birth”

Thankfully Williams was able to get the care she needed, but only after making repeated demands to get that life-saving care. Demands made to a team whose sole purpose was to watch out for the very signals she reported.

Some women aren’t as lucky. There’s 27-year-old police reform activist Erica Garner. Her enlarged heart condition wasn’t discovered until after she had a heart attack while giving birth to her son, Eric. As a Black child growing up in New York, the asthma that eventually hospitalized her was like a birthright. It’s easy to imagine a different outcome if Garner’s condition had been caught during prenatal care and monitored through delivery and in postpartum checkups.

There’s 39-year-old Kira Johnson, who’s scheduled C-section became fatal when she literally bled to death for hours from a lacerated bladder. Johnson’s “intractable pain” and her husband’s attempts to get her care were ignored until it was too late.

There’s Shalon Irving, a 36-year-old CDC racial health disparities expert who died from complications from high blood pressure three weeks after giving birth. And there are still many more women across class and income brackets whose deaths have yet to be told in the media, but who live on in the stories their loved ones tell the children they had no intention of leaving behind. There are those who know that they and their children are lucky to be alive after their birthing experiences.

We can’t afford to wait for policy to catch up with human decency. Lives are literally at stake. That’s why, as so often is the case, Black women and our allies are stepping up to provide resources and suggestions to effect real change in maternal mortality rates.

California-based Black Women Birthing Justice released a report, “Battling Over Birth,” that outlines the inadequate care Black women receive pre- and postpartum. It also provides recommendations on how to navigate prenatal care, doctors, and birth location. Women who give birth in “black-serving” hospitals are more likely to have complications, ProPublica reports. It’s part of the reason why there’s a rise in Black women interested in giving birth at home, a definite privilege for those who can afford the out-of-pocket costs associated with it.

There’s now more focus on the necessity for postpartum care in the six weeks after delivery. So much attention is paid to an infant’s well-being, but mothers need care, too. Postpartum checkups can help catch any lingering problems that could turn fatal if ignored.

Many Black women are becoming doulas, midwives, and reproductive health advocates to fight this battle, offering culturally sensitive support and care for women throughout their pregnancy and into postpartum. Healing Hands Community Project in Texas, which has the nation’s highest maternal mortality rate, created a program that helps Black doulas support Black mothers in Austin.

Black Mamas Matter Alliance is working to change the narrative through amplifying Black mothers voices, making policy change recommendations, and conducting research into this issue. Of course, that’s barely scratching the surface of the many individuals and groups out there joined in the effort to make birth a beautiful experience instead of a life-threatening emergency for Black women.

Serena’s story—and the media investigations and deaths that came before it—remind us of how fraught this experience can be.

We shouldn’t have to be our own doctors.

We shouldn’t have to be considered one of the greatest athletes of all time to have medical professionals eventually listen to our concerns about our health.

We shouldn’t have to be rich, or well-educated, or any number of other victim-blaming factors that we’ve learned ultimately don’t protect us. Crossing our fingers and praying isn’t good health care policy.

We know what we need. We’re talking. Hell, we’ve been talking. And it’s time for this country to finally listen and act.

The response to Serena’s story was so great on our Instagram and Facebook account, we’re going to work on a series around protecting Black women from traumatic and potentially fatal birth experiences. If you would like to contribute, please leave a comment or email info@matermea.com.