After completing her PhD in education, author and educator Tamara Pizzoli was prepared for a life in academia. But a devastating breakup led her on an adventure across the Atlantic Ocean to Italy, a country far, far away from her hometown of Killeen, Texas. It didn’t take long for her to fall in love with Rome and, soon, the man who would become the father of her children.

“I moved in September 2007 with a broken heart, met my now ex-husband in November, fell in love and married him in May,” Pizzoli says. “I never really intended to stay [in Italy]. But now, I’ve curated a life that truly reflects who I am as a person, and I don’t know if I would have been able to do it as easily in the States.”

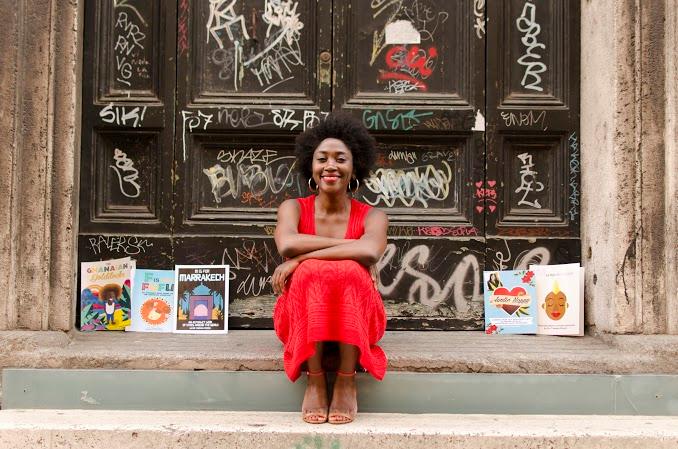

Today, Pizzoli lives in Rome with her children—Noah (6), Milo (3), and Zen, due later this year—where she’s penned a series of children’s books designed to more accurately reflect the multicultural world in which we all live. (The first, the award-winning, The Ghanaian Goldilocks, takes a gender bending, Afrocentric twist on the classic children’s tale.)

We spoke with Pizzoli about how she found the courage to start over, and how she’s adapted to life, love, and language in one of the oldest cities in the world.

How did you end up in Rome?

I was at the end of my doctoral studies. I’d been dating a guy who lived in Ghana for about five years, and I was really expecting to marry him. I was on my way to visit [him], and found out during a layover that he’d been cheating on me for a majority of the relationship. I didn’t get on the flight, and I stayed in New York.

A friend I was visiting had a little sister who would go back and forth to Italy a lot. She asked me if I wanted to have an adventure and move with her the next time she went. I finished up my doctorate in August of 2007 and moved to Rome—sight unseen—in September. I had my whole life planned out: I was just going get a job as a professor, wear scarves to work, and get coffee. But it didn’t work out that way!

Obviously, you’re enjoying yourself since you’re still there. Take me back to when you first got to Rome. What was the biggest culture shock for you?

Rome is one of those cities you see listed in fashion magazines with Tokyo, London, and New York. I was expecting it to be way more diverse than it actually is.

I didn’t move to a swanky part of the city at first. We found our apartment on Craigslist, again, sight unseen.

We ended up in a neighborhood that was so heavily populated with immigrants that I got out of the taxi like, “Where are the Italians?”

The area I was in [Piazza Vittorio], is an area known—especially at night—for high levels of prostitution. So I got mistaken for a prostitute quite a lot when I first got here.

That must have been interesting!

I was so naive! I was 25 at the time. People had to break it down for me.

I was teaching English at the time, and I had two students who were journalists and they were really cool. I would explain to them in conversation during our English lessons about what was going on in my life.

One time, I lamented that I was having such a hard time getting a taxi, and that everything else except for taxis would stop. They were like, “Oh honey, they think you’re a hooker!” It would have never occurred to me.

From what I’ve heard, a lot of the women of color in those areas at night are working girls. I’d have to say that I haven’t seen any, and hadn’t during that time. But apparently, that’s the case.

Was there a language barrier?

Most people speak Italian. I moved knowing “Ciao,” and that’s it. But I had Spanish. I was a kindergarten bilingual teacher for a long time, so that made it easier to pick up the language. It took me a couple of months before I could get by. It’s a city where you’re going to need to learn the language.

What is the best way to pick up the language?

I think for a lot of expats—especially Americans—it’s easy and convenient at times to stay to yourself or gravitate towards people who speak English. And of course the city is wonderfully welcoming to tourists. But I would advise against that. Make friends and have experiences with locals.

I moved knowing “Ciao,” and that’s it.

A lot of Black Americans have a fear of racism and not being accepted in a new country. What are your thoughts on that?

I think it’s a such a leap of faith, and it takes such courage to make this kind of a move. It’s almost best to prepare yourself mentally for whatever you find, and make the decision that you’re going to thrive no matter what.

I know people who’ve said that they’ve had not one racist incident, and I know people who’ve had tons. I produce documentaries and a web series. The first is called Black Girls in Rome. It highlights the experiences of 12 women of color who are living here. It’s interesting to see the range of experiences that are discussed in the video, but I don’t think it’s a guarantee. Nothing is a guarantee until you get here and see what happens.

How does your family feel about you being so far away?

My mom wasn’t very supportive when I first moved here. This is a woman who let her kid go to college at 16. But the prospect of me going across the Atlantic, she was just like, “No.” Now she comes to visit and we’re eating ice cream and taking these long strolls at midnight with no sense of danger, and she’ll say, “I’m so happy you live here. I’m so happy you’re raising your Black sons here.”

I think if you’re raising African-American males, the narrative that’s given to them is often not always one that’s positive. That’s not something I worry about here. On the contrary, I worry that my children are so doted on. They get so much [positive] attention for how they look that often times I’ll tell them jokingly, “If you were in Brooklyn, nobody would care.” There, it’s completely normal to have curly hair and brown skin.

What’s it like raising your children in Rome?

My ex-husband [who is Italian] and I moved back to Texas a couple of months after we were married. He was just a wilting flower in Texas. He couldn’t do it. We gave it two years. My oldest son, Noah, was born in Texas, and we moved back [to Italy] when he was 13 months. So Noah’s first language is actually English. If you ask him what he is, he’ll say, “I’m American.”

Milo, on the other hand, might as well be Roman. He prefers Italian. I’ll speak to him in English and he’ll respond to me in Italian. This child [on the way] will be African-American. His home language will be English, but he’ll speak perfect Italian by default. This is the world we now live in. Modern families!

Do you think about striking a balance between their African-American identities and their Italian identities?

It’s so important to me. I think it shows in the types of books that I write. There are six [books in the series] and they’re all very diverse. I want my children to acknowledge [their African-American heritage] because it’s real and it’s there.

Italian as a culture is kind of like parsley. Parsley is a bossy herb. I don’t like too much parsley on my pasta. Italian is a dominant culture. It’s strong. Their monuments from 2,000 years ago are still here, so I think a lot of other cultures when they come here feel like it’s an uphill battle, especially with the other parent.

If you have a mixed family, the [non-Italian parent] is going to have to fight—I mean truly lobby—to make sure that the other culture is maintained. It’s easy to get kind of swept up.

How do you make sure your culture is protected as you are raising your boys?

I’d have to say through creation. I make the books I want my children to see, and my books reflect the world that I want them to know exists, and to experience firsthand for themselves one day soon.

I suppose that started with The Ghanaian Goldilocks. For my boys, reimagining that famous fairytale in my eldest son’s likeness in a story that is set in West Africa is normalcy. It’s my belief that art is about presence. That’s what makes it so important. So through the diversity of my books, whether we’re speaking of location like in M is for Marrakech, or appearance like in M is for Mohawk, or learning about diverse foods in F is for Fufu, they’re constantly being exposed to a world around them that is comprised of so many wonderful, exciting people and things. Of course I read them other books as well. I don’t know that there’s any better teacher of important and powerful lessons than the nuance of great stories.

How did you get the idea to start writing children’s books?

The first book was inspired by my oldest son. When Noah was about 3, he had this adorable afro that would get light on the ends in the summer. He was always very kind hearted and respectful by nature but, like any kid, very curious.

One day, we were at his uncle’s house and he was in the kitchen touching things he had no business touching and tasting things he had no business tasting. I said, “Who do you think you are, Goldilocks?” and he just died laughing. He thought that was so funny.

So that’s where the idea for The Ghanaian Goldilocks came from. I thought, why not turn the story completely on its head, and have Goldilocks be a brown boy with a golden-tipped afro? The illustrations are based on Noah, and because I’d been to Ghana so many times before, I had a lot to pull from from the culture.

I want my children to acknowledge [their African-American heritage] because it’s real and it’s there.

As I wrote, I found the Ghanaian culture yielded itself so nicely to the story, so instead of porridge, there’s fufu; instead of chairs, there are stools; and then you have this possibility of having a really principled resolution at the end. It feels very West African in the sense that there’s always a lesson, and Goldilocks doesn’t get shamed at the end. I wrote it with myself in mind as a parent, just as much as I did with my kid.

I strongly believe that art is about presence, and that’s what’s so exciting about the times that we’re in right now. Whether it’s about YouTube videos or Instagram. We’re past the time where you have to wait for someone to acknowledge your perspective as valid and put their money behind it. I found my illustrator on Twitter. I self-published my books. If you have an idea, you’re as good as published, once you decide to write.

As an educator and a parent, what are your opinions of the school system in Rome?

I’m getting heart palpitations. I want to sing a Negro spiritual. Times is hard. It’s tough. I’ll admit that I can be pretty snobbish when it comes to what I expect from education, because I am an educator. When it comes to early childhood education, I know what it’s supposed to look like. I used to own a language school here in Rome, but that was more out of a necessity and a desire for my kids to have a proper foundation in English.

English in Rome is big business, and if you have enough money to start a school, you can start a school without necessarily being qualified to do so. The school where my children attend now is owned by my ex-husband’s family. No shade, but nobody speaks English in the office—not even the director—but it’s supposed to be a bilingual school. So they can’t attend there next year, because I need the communication from the office to be in proper English. It’s tough.

There are wonderful international schools that are going to run you, like, a Honda a year. And I’ve heard mixed things about public school. I used to have private students who were Italian and brilliant. I’m talking middle school kids who were going through the Italian public schools and these kids would have run circles around me academically when I was in high school. It’s a different approach, but they also have a really complicated system in which you have to kind of know your career path right after middle school. I don’t know what I’m going to do! I homeschool both of my kids even though they also go to school.

What is the cost of living like in Rome?

I think the average family of four in Rome lives in a 70-80 square meter (753-861 square feet) apartment, and they make incredibly good use of their space. Living here so long, I’ve fallen in love with tiny spaces and innovative ways of using nooks and organization. I think you can look at the $1,200-1,500 range for a one, two bedroom apartment, maybe even $800-900 for a one-bedroom.

I live in the middle of Rome on one of the most beautiful streets, and I found my apartment because of the economic crisis. So I think it just depends. There’s a site called Wanted In Rome that I used to find my apartment. You’ll see these beautiful apartments overlooking the Coliseum and sometimes they’re just $1,000. If you’re a person who can have multiple streams of income, you can make it work. Here, the average salary is like $1,000 per month. I joke with my friends that a lot of Italians make it because they inherit their homes and have these huge support systems. A lot of my friends have the luxury of relying on their children’s grandparents for help. so that’s a huge savings. Then if you live in a place that’s well connected to transportation, you don’t really need a car.

What advice would you offer families considering a move to another country?

Be brave. Have money set aside. Don’t tell anyone your plans who isn’t going to support you. Research the [country] and where you’re going to stay very well, but also don’t overthink it. A lot of the beauty lies in the whimsy.